Part 1 learning series

We all need to learn lifelong, that’s obvious. However, learning is an activity that requires effort and time and implies leaving our comfort zone. Sometimes this effort is small, other times it may require a big push and lots of time. If learning does not come by itself and requires effort from our brain, then what are the reasons to start learning? We distinguish at least four important drivers of learning. Let’s find out!

1. Out of necessity

A change in our environment often gives us no other choice but to start learning. Popstar Kylie Minogue, for example, saw little choice but to teach herself Logic Pro (i.e., ‘software that turns your PC into a recording studio’) during the first lockdown as she couldn’t physically go to recording studios. Learning out of necessity perhaps doesn’t seem like a choice made out of consciousness, but in the end, we do make a choice. What’s more, while some people start learning forced by change, others ignore the change and start behaving victimised or exhibit other counterproductive reactions.

From an employability point of view, we could argue that ‘learning by necessity’ is a reactive response. Often it’s a little too late, and in the worst case there may even no longer be an opportunity to start learning.

2. ROI-driven

As mentioned before, learning takes energy and consumes time. That’s why we make a decision – consciously or unconsciously – before we fully dedicate ourselves to learning something comprehensive or difficult. In a way, we perform a ‘Return On Investment analysis’ and ask ourselves questions like:

- Do I expect to be faster after my learning effort?

- Will I be included in the group sooner?

- Am I more likely to get a promotion?

When digital photography made its appearance, for example, it was scorned by many photographers because of the initially limited quality. As the quality and possibilities increased, it became clear to many that digital photography had several advantages to offer, such as a faster workflow and non-destructive editing. This insight made photographers realise that – if they wanted to remain competitive as a professional – they would have to invest in digital equipment. Above that, they needed to dedicate time and energy to learn how to use the associated editing programs. Thus, there’s a ROI consideration for both the equipment and the learning effort.

From an employability point of view, we could say this is an example of just-in-time learning.

3. Curiosity

When we learn out of curiosity, we do not necessarily expect a positive return in the short term. It’s about the urge to understand something an sich. For example, some people learn several languages just for fun. Or, many engineers want to understand how things work, even it is far outside their area of expertise. Some people visit museums just to broaden their horizons. Certain musicians learn another instrument to better understand the interplay with their own instrument in an ensemble or band setting. Also, our curiosity is often already satisfied when we read books or watch movies about a particular topic.

From an employability point of view, we could say this is a form of explorative learning.

4. Self-development

Self-development fuels a spontaneous and continuous desire to learn because it concerns ‘competences’ that we consider to be an essential part of our own identity. Musicians, for example, may create music, but they are first and foremost a musician. When ‘being a musician’ is an important part of someone’s identity, it creates a sustained drive to improve musical skills. At the age of 90, Toots Thielemans still enjoyed finding new chords and chord combinations. “I study and practice more than ever”, he said at a blessed age. A developer who sees ‘programming’ as part of his or her identity doesn’t need to be encouraged to learn the latest developments in their field. He or she already has figured it out before the ‘organisation’ discovers these new developments.

From an employability point of view, we should not be concerned. Self-development is true mastership: a continuous desire to become a better version of oneself.

The NRCS model

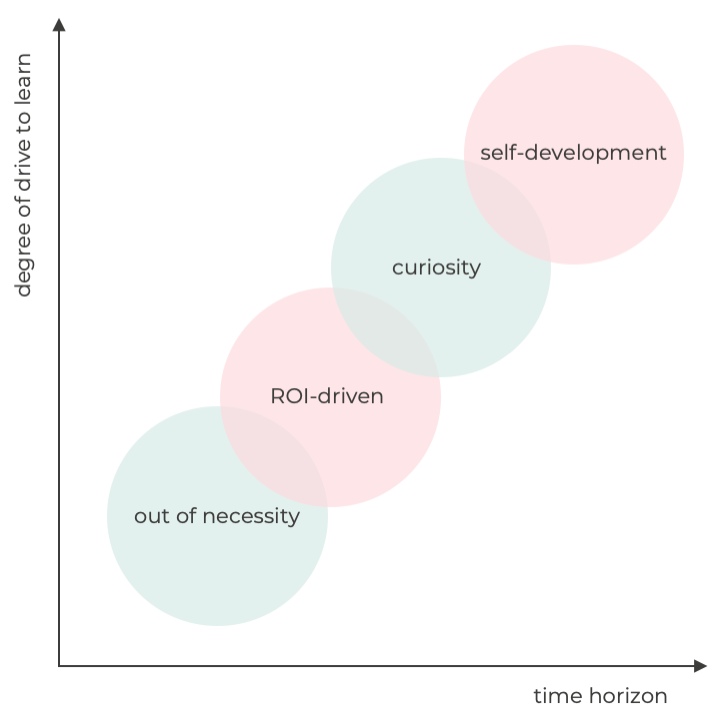

The NRCS model summarises the four important drivers of learning: necessity, ROI-driven, curiosity and self-development.

The horizontal axis illustrates the time horizon. When learning out of necessity or ROI-driven, we expect or hope to realise a positive outcome in the short term. This is less the case with learning from curiosity and in the context of self-development. Those who pursue mastery have trust in the learning process. He or she knows that learning, and especially perfecting our skills, takes time and practice.

The vertical axis illustrates the degree of the drive to learn. With learning out of necessity and ROI-driven learning, we rather speak of a willingness to learn, while there’s clearly a hunger for learning with learning out of curiosity and self-development. Note, willingness to learn or hunger for learning do not necessarily have to coincide with extrinsic and intrinsic motivation.

Starting to learn is more than a motivational given only. In the next blog, you’ll learn about ‘learning anxiety’, a not to be overlooked aspect of learning. Stay tuned!